Founder's Page

About Treenway Silks Founders

Karen Selk and Terry Nelson started Treenway Silks out of their home in British Columbia. Over they years they worked as a team learning about importing silk fibers, dying silk, and using silk creatively. All the while raising a family and being part of a vibrant northwest island community.

This page of the Treenway Silks' website continues their story, as they remain an inspiration and priceless resource of knowledge and creativity.

August, 2011 - TREENWAY HAS SOLD! -

Susan Du Bois and Richard Yabunaka from Lakewood, Colorado excitedly purchased Treenway Silks. They will be carrying on with all the same high quality products from our trusted suppliers and are looking forward to serving you in an efficient, helpful and friendly manner. We are very confident Susan and Richard will carry Treenway forward in style. We are dedicated to continue working with them for a smooth transition.

Karen & Terry were busy getting ready to pass Treenway Silk's ownership to the next generation. Here are some photo highlights.

Sept. 2011 - Even Busier Than Ever

Karen and Terry are enjoying their retirement, but they may be even busier than when they owned Treenway Silks! In the past six weeks, they've been able to take a couple of short vacations, visit family, meet their newest granddaughter Anita (born August 17th), entertain friends, and, of course, work in their fabulous, massive, organic garden which is producing a bountiful harvest.

From Karen: "We knew the rain was coming so Friday we did a huge harvest of many things. The quinoa was the most exciting--it is such a beautiful grain! This will be enough to feed us for the year"

"After the harvest and putting food by is complete, we are off to India. Remember those Asia Journals in the newsletter? I have been working hard on the outline for a book which will pull together 25 years of travel and research about silk."

We can't wait to hear more about Terry and Karen's India trip! And we eagerly await a publication date for Karen's Asian Journal book!

November, 2011 - India Trip (Part 1)

By Karen Selk

With Gratitude & Appreciation

We have been chatting with you by phone, letter, email and the newsletter for 35 years. We have had the time of our lives starting and nurturing Treenway and feel extremely grateful to have been selling such an amazing product as silk to such an amazing group of people. We sing your praises as the nicest people to do business with to other types of business folk. We have made mistakes and almost always you have been kind and understanding.

We thank you from the bottom of our hearts for all the support, kindness and laughter through the years. You are truly appreciated. It has been such a joy and we will miss you.

Best wishes to you all,

Karen & Terry

Karen's Classes/Workshop & Conferences

Karen will, of course, be busy doing what she thrives at - crafting with silk fibers.

You can stay informed on her schedule through Treenway Silks emails. Be sure and sign-up for the Treenway's newsletter! And her schedule will be available here on the Treenway Silk's website → Workshops

Getting to the Station on Time

In the dark hotel lobby, the sleepy night receptionist rises from behind the counter wearing a knit hat and jacket at 4:45 am, “Yes, madam?” “We have a hotel car booked to take us to the train station.” A confused and panicked look crosses his face as he turns on the light and looks through some papers on the desk and replies, “No, madam.”

We explain how we made the arrangement the night before with the hotel manager. Some shouting ensues and the night watchman from outside lifts the grate in front of the hotel doors and enters. There is much discussion. We explain again about having to catch a 5:30am train, and then we remain silent. We have traveled here many times before. We are calm on the outside and inside. We know somehow we are always taken care of by the people of India and the will of god.

Hands wave, heads nod and bob and a three wheeler transport appears. Much discussion again as the price is set for the journey to the train station. The fellow from the hotel pays the “taxi” driver and prompts us not to pay again. The morning is chilly in the open air ride through Bilaspur in the dark of the early December morning. The drive through the city goes straight rather than weaving back and forth through the usual obstacle coarse of cows, scooters, bicycles, cars and mobile carts of food, newspapers and other sundry goods as most everyone is still in their homes.

Upon reaching the train station we look at the red flashing message on the board change from Hindi to Urdu to English. One fellow, then 3 fellows ask if they can help us. We ask from which platform the Gondana Express is leaving. After much head bobbing and hand jestures we are told to walk over the flyway to platform number 3. Once there we check again with a young woman to ensure we are in the right place and she concurs.

The train arrives and we have to run as our car is way at the back of the train. It is a sleeper, curtains are drawn and everything is dark. With our flashlight we peak into the compartments. We find our berth, but people are sleeping in it. We ask again, if this is the right train. “Oh my gaud, no! Quick get off.” We fumble and stumble off the train and are directed once again to another platform. We now know where our car number will arrive, so we walk to that place. As the train slows, Hansraj jumps from the train, all smiles and warm hand shakes. Our 7 hour journey to the tribal area of Bhandara to see how peduncle yarn is made, begins.

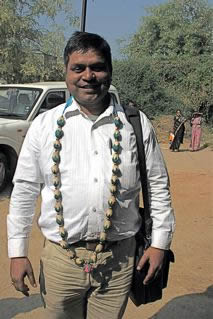

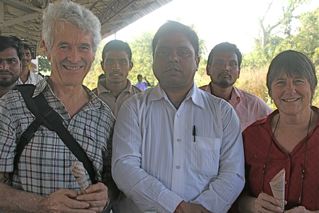

Hansraj the Silk Merchant

Immediately we like this jolly man. Upon settling our luggage under the seat and greeting our other berth mates Hansraj opens his pink and purple quilted bag and places a handwoven tusar (tussah) scarf around each of our necks. We begin exchanging stories of how many children we have, what is the average summer and winter temperature of our home places, and never stop chatting for the whole seven hours.

Hansraj is a 38 year old silk merchant with an amazing heart and story. We will introduce you to his uncle, where Hansraj’s interest in silk begins. His uncle worked for Eastern Silk Ltd from Calcutta for 10 years, some 50 years back. This company had a production centre in Orissa state, just south of Calcutta. The uncle left the company in 1972 and started is own silk business in Orissa.

Hansraj was a history professor in 1995 when his uncle called him to help out because he was ill. Hansraj could not help but become totally fascinated with silk and the people that raise and spin and weave it. He found his work in the business to be more satisfying than teaching because he is helping the poorer indigenous people who raise the wild silk find a market for their work. He says, “They (the indigenous people) have traditional knowledge from their parents, no book knowledge. When we purchase products, not only do I purchase their goods, I purchase a smile from the people”.

They are a small family business. They provide anything silk that a buyer requests. Hansraj is married to Pooja and they have two boys aged 7 and 10. Quality control for all aspects of the business is carried out by themselves.

Pooja is responsible for fabric production, their uncle is responsible for production in Orissa state and that leaves everything else for Hansraj including overseeing the stitching of some goods on the other side of the country in New Delhi.

As well as Orissa state, they have production centres in Jharkhand and Chattisgargh states. We visited two of the productions centres. The name sounds big, but in India it means a village that concentrates most of its man- and woman-power on any aspect of textile production. Most of their sales are in India, but they also export, with Japan being their biggest overseas customer. More sales means they can keep more people working on a constant basis instead of just when the orders come in.

We, the Treenway Silks family of Karen and Terry and now Susan and Richard, started doing business with Hansraj in 2009. We will be honest, it is always scary and risky to start new business relations with someone overseas. We had visited one of Hansraj’s productions centres when we were in India in 2007, so we had an inkling of the quality and ethics behind the company. Not only have our business dealings been timely and just what we asked for but Hansraj can produce in the quantities that are doable for a small company like Treenway Silks.

Peduncle Yarn Production Center

The tropical tasar (tussah) cocoon looks different than other types of tussah. This caterpillar does its hatching from the egg, eating and spinning outside in the forest. Because of this, their cocoon making process is unique. They start by spinning a peduncle or very stiff stem, much like the stem of an apple. They attach this stem around a branch of their food tree with a ring. After one full day of making the peduncle, they finally start to spin their cocoon.

The peduncle is a nearly black colour and extremely stiff with sericin, the “glue” that binds the filaments of silk together. Nothing in the production of silk is wasted. Until 50 or 60 years ago, the peduncles were used for various things, but not a readily usable yarn.

The village production centre where the Treenway Silks peduncle yarn is made is a heartwarming story of a woman and husband entrepreneur team. Rekha is from a traditional tasar weaving family for over 200 years. Traditionally they did their own reeling and weaving.

Ten years ago she and other women from the village traveled to the Gandhi Ashram Sevagram, which is called a Gandhi centre, for spinning. Here they trained on a machine for spinning cotton because they saw the potential for spinning silk peduncle. Peduncle fibre is very short and not possible to be spun on a big machine.

After completing their course, the Gandhi ashram provided them support to purchase a spinning machine. The machine is hand operated, but can spin 6 yarns at one time. It is a step between takhli (drop spindle) spinning and industrial machines.

Most of the women in the village come from a weaving family. Rekha employs 20 to 30 women for weaving, 10 women for peducle spinning and 11 other women are involved in dyeing, block printing and embroidery. Rekha winds the 100 metre warps for the weavers using something similar to a sectional warping method. The weavers can weave 2-3 metres per day of plain weave cloth.

Making Peduncle Yarn

Most villages involved in any form of making textiles are also agriculture based. It was rice harvest time when we arrived. Most of the women and men were out in the fields or thrashing the grain. Of course Rekha was well aware of our visit and prepared the day before for our arrival and a clear demonstration of the process of making the peduncle yarn.

The peduncles are soaked overnight and boiled for three hours in water, soap and washing soda, at a ratio of 1 kg of soda to 8 kg of peduncle. This is to soften and remove most of the hard sericin.

-

The mass of fibre is washed in clear water.

After squeezing out the water, the fibre is set out to dry in the sunlight.

After drying, the fibre is beaten on the earthen courtyard with a bamboo stick for approximately one hour.

The first carding is done on a narrow hand crank carder with a coarse belt to make a wide ribbon of fibre.

The second and third carding is done on the same type of machine with a finer cloth.

Another small hand crank machine with a series of rollers pulls and stretches the fibre into a narrow tape. The fibre is put through this machine 4 times.

A sliver is made by inserting two rovings side by side into a hand crank machine that puts a small twist into the fibre as it further pulls and stretches the fibres as they drop into a can receptacle in an organized circular “pile” of sliver.

Six of these slivers can be spun simultaneously onto six separate bobbins making the peduncle yarns. This spinning machine is also hand crank and is efficiently set up to perform two tasks at one time. While spinning the yarn, a skein winder at the top of the machine winds yarn from a bobbin into a skein. The peduncle fibre is very short and the yarn breaks frequently while being spun. The operator must stop and twist the fibre to continue the yarn where the break occurred. Even with this slow down, a woman can produce twice as much yarn in a day, compared with spinning on a takhli (drop spindle).

The Peduncle Center Village Culture

It was a lovely afternoon with the energetic Rekha who is 35 years old and has two boys, 11 and 9 years old and a 13 year old daughter. We had chai and biscuits as she showed us all the beautiful products they had produced and were getting ready to take to a fair. [Photo 1 = Rekha's mother, Rekha's daughter & two sons, and Rekha. Photo 2 = Rekha displaying a piece of woven cloth to be sold at a fair. ]

This is an encouraging look at what can happen when tradition and an entrepreneurial spirit mingle. In many regions that once had a tradition of spinning and weaving, these arts are dying out. Just like the family farm in North America, it is too difficult to come back, once it is left behind. But this cottage industry provides work for whole families in a village.

Before starting this business ten years ago, many of the men were involved in the anti-social activity of smuggling coal to provide enough money for their families. We saw some men involved in this practice and it was grueling work. They tied 500 lb of coal in gunnysacks onto their bicycles. It was obvious they could barely keep the bicycles balanced and upright as they pushed them down the roadway. We wondered how they ever righted the bicycles after they put them down to take a rest in their sometimes, 70km journey back home. Hansraj explains the indigenous tribal people seem to be happier people, because they depend on nature to make their living.

As always when in a village, we lost track of time and had to race for the return seven hour train journey back to Bilaspur.

We napped and then chattered on about peduncle and the different tasar breeds, which ones give the most shine and the finest cloth. Hansraj has embraced his business not only from a financial aspect, but also knowing his product and the people that produce it inside out.

“Personal relations make good business” was something we all agreed upon as we chugged down the track. Not only is trust and friendship established, but smiles are put on peoples faces.

November 2011 - India Trip (Part 2)

by Karen Selk

Shopping for Eri

November and December is rice harvest time all over India. Most family members are out in the fields cutting, stacking and bringing in the harvest on bicycles, bullock carts, and by shoulder carriers.

Eri Catapillars

It is a good time of year to see eri silkworms, because that is an ongoing task all year round. But it is not a good time to see women weaving or spinning. Eri is called poor man’s silk, because it does not have the same shine that any of the other silks have, but it is beautiful none the less.

In between other daily chores women can raise five to eight crops of eri caterpillars per year. There are approximately 20,000-25,000 caterpillars per crop. The main food source is caster plant which grows like a weed everywhere.

The caterpillars come in a rainbow of blues, greens, yellows and creams with soft tipped spikes on each polka dotted segment of their body. Walking into a village with a porch strung with bouquets of caster leaves laden with multi-coloured caterpillars made us gasp with excitement. These caterpillars were 3 or 4 days away from spinning their cocoon, so they were heavy with silk.

Unlike the other types of silk producing caterpillars, eri does not spin a complete cocoon. They spin awhile and then stop, spin and stop. This leaves one end with an opening. This means the cocoons cannot be reeled or unraveled. They must be soaked in water and pulled making little “cakes” or hankies to be spun. In the villages most of the eri silk is spun on a takli, hand spindle.

Unlike the other types of silk producing caterpillars, eri does not spin a complete cocoon. They spin awhile and then stop, spin and stop. This leaves one end with an opening. This means the cocoons cannot be reeled or unraveled. They must be soaked in water and pulled making little “cakes” or hankies to be spun. In the villages most of the eri silk is spun on a takli, hand spindle.

Eri is also the silk that many people refer to as Ahimsa, peace or vegan silk, due to the hole in the cocoon. It can only be spun and this COULD mean the pupa is not stifled before making yarn. In reality, the protein rich pupa is very valuable as people food, animal food and fish food. The village people reach in to the cocoon and take out the pupa at just the right time for maximum size. They use it themselves and sell it for up to three times as much as they get for the silk. Very Interesting!

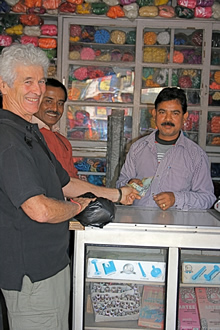

Purchasing Eri Yarn

Our mission on our last day in Assam, on the way out to a village was to find eri yarn. We were so amazed that we had not found any in all the villages we visited to see the raising of eri and talk with the women. But they had used all their yarn before the rice harvest and would not be spinning for some time yet.

What would seem a simple job in our country turns into an adventure with many people involved. We stopped at a government silk station to ask where they thought we could find a vendor that would have some eri yarn. After a big discussion a man got in the car with us and traveled on to the next town. He was sure there would be someone there with the yarn.

We walked the streets and finally saw a big sack filled with eri cocoons on the sidewalk next to a shop selling plastic buckets. Tucked back off the street was a small yarn shop. We asked the vendor for some takli spun eri yarn and he disappeared into a space smaller than a closet and reappeared with the yarn. We were excited and began the negotiations.

We walked the streets and finally saw a big sack filled with eri cocoons on the sidewalk next to a shop selling plastic buckets. Tucked back off the street was a small yarn shop. We asked the vendor for some takli spun eri yarn and he disappeared into a space smaller than a closet and reappeared with the yarn. We were excited and began the negotiations.

Sales never happen fast in India. One studies the product. The price is set and then the slow process of skeining it up just right, weighing it, then finding the perfect size bag and finally the long process of writing out the receipt in triplicate by hand, inserting pieces of carbon paper between each copy. That is not all. The vendor did not have the correct change, so he went on a sojourn to find another vendor that could make change for him.

Kazirange National Park

Through the years of traveling to Assam, we have made numerous trips to Kaziranga National Park. This park is home to the Asian one horned rhino. There is only one other place in India that has these rhinos. Kaziranga is a very great success story of helping these animals out of near extinction back to healthy stocks due their militant rangers. The horn of the rhino is coveted as an aphrodisiac in China. Over the years the animals have been poached for their horn only and the rest of the animal left for the vultures and other predators.

Through the years of traveling to Assam, we have made numerous trips to Kaziranga National Park. This park is home to the Asian one horned rhino. There is only one other place in India that has these rhinos. Kaziranga is a very great success story of helping these animals out of near extinction back to healthy stocks due their militant rangers. The horn of the rhino is coveted as an aphrodisiac in China. Over the years the animals have been poached for their horn only and the rest of the animal left for the vultures and other predators.

We stay at the same resort in the park, Wild Grass with our friend Manju. Every time we arrive I chide him because he still has cotton upholstery on his dining chairs. The first time we visited in 1989, I strongly suggested he should have eri fabric on his chairs. This visit I laughed when we walked into the dining room and scolded him for the cotton coverings. He answered that now all the other resorts had eri or muga as upholstery and there was no longer any need for that. I bemoaned the fact that he could have been the first before anyone even cared about indigenous products.

He did not rise to my kidding, but he listened once again to exactly what I wanted to do with the planned book I want to write. He was extremely encouraging. He loves his native state of Assam and thinks it is important for other cultures and Indians alike to know more about the wild silks.

He was very excited to hear how things have changed for the people who care for the caterpillars over the last 23 years that I have been going there to research. “The things you have seen from the old India to the modern India are rich with history and change. It will be very valuable in telling your story.”

The Eri Scarf

Just a short walk down a dirt road from Wild Grass is Rup’s little shop, filled with woven products from the self-help women’s group she started. She has many cotton items, but I was pulled by the muga and eri products. Shawls and scarves made of handspun yarn from the eri caterpillar and muga caterpillar both indigenous to Assam.

Purchasing your eri yarn and shawl was not just shopping, it was as most things are in India, an adventure.